If you have a glass box divided by a partition with a small hole in the partition...let's say the box is one cubic foot...and in that box you have 2,000 molecules of air (let's hope it's tempered glass), you would expect, because of the random motion of molecules banging around in the box and finding their way through the hole, that over time the number of molecules on each side of the partition would be equal. If you make two observations of the box over a period of a half hour, and in one of those observations you "see" that there is one molecule on the left side and 1,999 on the right; and in the second observation you notice that there are 999 on the right and 1,001 on the left, you naturally assume that the second observation occurred later than the first.

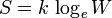

What do you mean by "later?" That's what Ludwig Boltzmann couldn't let go of, and so, like any good mathematical physicist, or student of probabilistic mechanics who wanted to be known as the founder of rigorous thermodynamic theory, Ludwig came up with the formula above, which lays it all out. His grandfather had been a clock maker in Berlin, so perhaps it was natural for Ludwig to wonder not only what time it was, but why time it was.

Our sense of the passing of time is based upon a random increase in disorder in all things physical. Boltzmann's great insight was that the glass box arranges itself the way it does because of the laws of chance, of aleatory development. There is precisely one arrangement for all 2,000 molecules on the left and none on the right. There are 2,000 arrangements for one molecule on the left and 1,999 on the right, one for each molecule taking its turn as Han Solo. There are almost two million for two on the left and 1,998 on the right. There are about 1.3 billion for 3 on the left, 1,997 on the right. For 1,000 on the left, 1,000 on the right, there are about 2 x 10 raised to the 600th power. So the odds favor the roughly even distribution, in the same way that you expect 10,000 coin flips to produce about 5,000 heads, 5,000 tails, even if the first seven or eight flips are all heads.

Thus, the statistical basis for entropy. The formula above is on Boltzmann's tombstone in Vienna, and some scientists believe the formula belongs in the same category of breakthrough as Einstein's formula for E or Newton's laws of motion. I've been reading about him in Sean Carroll's From Eternity to Here, which is all about Time, in all its manifestations. Carroll is a Caltech physicist who seems to have picked up some of Richard Feynman's gift for mixing the sublime with the ridiculous, such as quoting Bill Murray's Peter Venkman from "Ghostbusters" when he wants to make a heavy point: "Move back, I'm a scientist." Or quoting from "Annie Hall," as when little Alvie Singer becomes worried about the expanding universe and his (Jewish) mother tells him sternly, "What has the universe got to do with you? You're in Brooklyn. Brooklyn is not expanding."

I actually take a great deal of comfort from the realization that chance lies literally at the bottom of everything, that we know what time it is because disorder and randomness keep increasing, and have since the Big Bang. It shows up everywhere. Feynman's own example was typically brilliant and evocative: you're on a tropical beach and it suddenly begins to rain, torrentially. You grab your towel and run for cover. The towel is a little "less" wet than you are, so at first you're able to dry yourself a little with the towel, but after a minute or so, you're simply trading the dampness of the towel for the dampness of your body in a pointless exchange of water. That's entropy, the point of equilibrium.

Thus, the more energy you expend during your life, the greater the trail of disorder in your past (where it belongs). That seems about right, doesn't it, when you think about the lives of marvelously energetic and accomplished people. Their lives are often a mess. Jimi Hendrix, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (another Austrian entropic), Jim Morrison, Vincent Van Gogh, all burning brightly, all dying too young. Maybe they just knew something the average mortal does not: we're actually meant, by Nature, to unravel, or even, as the greatest writer of all time, who himself died at the age of fifty, put things,

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew! Even Feynman died too young, if you ask me. Any state of the world is the poorer for not having Richard Feynman in it, a disordered and expended state. One might think of the entropy of democracy, for example: a room with 2,000 people, and one side, at the lectern, is Richard Feynman, and on the other are 1,999 people...